621 Miles of Recognition

Nomadness has completed her shakedown cruise — covering 621 miles in 2.5 months. This is a languid pace, in geographical terms, but the experience gained was considerable… enough to induce a near-total inversion of the project priority list, satisfy a host of initial learning curves, smoke out the weaknesses of the ship, and advance to the next level of confidence. (The latter is no small matter, as the notion of seaworthiness applies at least as much to the brains of the crew as the bones of the vessel.)

The journey itself was mostly spectacular, underscoring the nature of the Pacific Northwest as a sailing destination. We’ve experienced everything from balmy days to 40-knot gales (docked for those, mercifully), felt the quiver as Nomadness put her shoulder down in 25-knot winds, puzzled over engine anomalies while drifting toward leeward cliffs, tangled anchor chains with a whimsical neighbor, cozied around the new woodstove on a cold night, probed the innards of the ship to reverse-engineer ancient mysterious subsystems, found new friends on exotic shores, dinked and paddled into various skinny places, circumnavigated islands, reawakened the technomadic flotilla plan, and solidified a clear concept for an integrated ship information system. Those mileage statistics… still ludicrous in boat-amortization terms… mean nothing in the context of the raw experience itself.

Still, we’ve done 621 miles. A good start. Here’s the GPS track of the journey overlaid on Google Earth and stitched into a single big image (you can click the picture to see it larger, but there is also a clear, vertically scrollable version):

I’m no more a fan of straight lines than I was during the convoluted bicycle tour of the US; the tangled track is part of the fun, the live low-resolution version via APRS even more so. I’d get email while underway: “hey, looks like you’re making pretty good time!” Seeing more and more tracking systems for sale in the marine marketplace, complete with $20/month fees, I think I’ll throw together a quick how-to and use it to kick start the new article series.

Publishing

Ach, so many projects. It could easily spin out of control, but the pace of sailing has reminded me of my old adage that you can accomplish amazing things by simply moving in the same direction for a long time. Another trick is a twist on the rule-of-thumb that applies to anything taken on a bicycle or boat: every piece of work should be useful in multiple ways, in this case translating into a publication “product” that corresponds to any new design, hack, fix, or notable discovery. What this means in immediate practical terms is that the next few months should see a succession of boat-related jobs interspersed with online articles, PDFs, or print monographs detailing pieces of the system.

In this broken economy, the timing is good for this kind of micro-publishing… folks want to avoid the insanely expensive marine service industries, and for good reason. I’ve been burned already with overpricing, and even the guys who pull down big hourly fees don’t necessarily deliver quality any better than one can achieve with some good old-fashioned DIY effort and a handy assistant. After having to fix two expensive jobs by professionals, I am feeling the need to do my part to distribute much-needed how-to material to offset an industry that has become increasingly intimidating. Manufacturers aren’t making this any easier with their documentation, good tech support is hard to find, and there are marine dealers who are profiting hugely from the forbidding complexity of essential technologies.

So that’s the Nomadic Research Labs business plan… becoming a writer again while fine-tuning the technomadic survival/escape/adventure pod. There’s plenty of room in there for some proper gonzo engineering, methinks.

Imminent Geekery

So, what’s coming up? Earlier I mentioned the inversion of the priority list; this translates into making sure self-sufficiency tools are in place before getting too carried away with seductive techno-wankage. Now that the ship has a wood stove (which works great, by the way – five fires so far), the immediate next steps involve the Katadyn 40E watermaker, Outback power management system, some kind of bow thruster, Isotemp water heater, enhanced comfort, the essentials of the communications console, outside helm chart plotter, and the on-board web server.

The latter might sound like it’s straying into that non-essential category, but more and more of the problems come down to a centralized information resource. A dedicated Mac Mini will run MAMP, Joomla, WordPress, and Ruby on Rails… becoming the core system for almost all ship operations (and it’s small/cheap enough that in addition to continuous LAN backup I can carry a whole spare sealed away in case of disaster). I’ve already got Joomla and WordPress running under MAMP on the laptop, and it’s a sweet environment.

What justifies all this on a sailboat? Well…

First, the boat came with a very handy manual assembled by the previous owner, running through basic procedures for all on-board operations (it was chartered three times, for a week or two each). This has been helpful in my learning curve but is drifting out of sync with reality, so I’m re-doing that class of content in the form of a local Joomla website… one short procedural how-to for every action that has to be performed on the boat (emptying holding tank, starting wood stove, dropping anchor, starting engine, and so on).

A second menu tree in the same site carries technical information about all components and systems on the ship, including PDF documentation, drawings, and any other relevant material. This is augmented by the “NOIDS” devices-and-links relational database (in FileMaker), also published to the internal web.

The third section of the “static content” server is for ship’s logs, maintenance records, fueling history, spares, inventory, and so on… though WordPress might be quicker for updating logs and personal observations.

So far, this is all pretty traditional webbish stuff, and is almost trivially easy to set up. The next layer gets a bit more challenging: bringing together all the data sources into some kind of coherent view of the boat, accessible on the local console, any laptop in the LAN, or remotely via dynamic DNS.

Here, we have to pull together quite a mess of information. The NMEA 2000 network includes a Maretron USB interface; I haven’t clawed my way into this enough yet to be 100% certain it can live outside the Windoze environment, but I’m betting it can… and it will feed all the PGNs corresponding to the network of devices around the boat (GPS, compass, masthead wind data, depth, power, rudder angle, fuel tank levels, and so on). At the same time, National Instrument 6008 USB interfaces slurp in analog and digital data points (hatch and other security sensors, bilge pump cycling, temperatures from all over, states of circuit breakers, dedicated system sensors, and other random stuff). What to do with all this?

Well, basically it all gets dumped into a database (SQL), along with time-stamps. This is where Ruby on Rails comes in, providing the framework for a “database-backed website” and allowing such niceties as overall power status screens, live display of the plumbing, detailed security sensor map, and historical plots of measurements to aid in diagnosing problems. Other clients of the same pile of data include the voice-response system that allows DTMF queries via handheld ham radio, selected telemetry transmissions as a function of available bandwidth, monitoring scripts for alarm conditions, and a simple command line interface that will work over very thin pipes (packet). There is also an always-on micro that sees a subset of everything I mentioned, capable of initiating an emergency response during times of extended power-saving when the Mac is powered off.

That takes care of the whole input side, but there’s also a lot of active intervention necessary — the kind of stuff that usually translates into front panels full of switches. This will be done with USB latching relay boards which manage PTT-steering and control of the radios, power switching, video routing, and other tasks that involve direct control from the browser front-end or simple scripts. Video, for example, has to route 8-10 analog sources around the boat to three monitors, a recorder, and an IP video server that lets any of the channels be remotely viewable as a webcam. (I wish I had this right now, in fact… one of the cameras is a sealed miniature unit mounted atop a remotely steerable spotlight on the bow… it would be nice to peer up and down the dock from here in my office and occasionally turn around to gaze across the expansive foredeck, check for seagulls, and initiate a squawk from the hailer horn if so… or at least say hello with the speech synthesizer to startle passers-by. I know. It’s a sickness.)

Finally, this Mac at the heart of the boat will run all the normal day-to-day applications, as well as MacENC navigation software, which has proved itself well during the recent adventures. With a Planar or Argonaut marine sunlight-readable display at the helm, I may end up completely removing “appliance chartplotter” from my shopping list.

So. It keeps creeping up in priority, this gizmology: a big part of the “mission profile” of this project is to integrate layers of complexity into something that feels as simple as possible, yet makes it easy to implement new ideas without having to build or buy more gadgets. Doing that means starting with a solid and extensible architecture, making sure everything is interfaceable, adding sensors to stand-alone units, bringing all signals into a central area (analogous to all lines returning to the helm), avoiding vendor or standards lock-in, and thinking it through before getting too far into construction.

There sure are a lot of ways to do this. I’m daydreaming about geekery even when at the helm:

Bow Thruster Redux

Finally (and briefly), the bow thruster issue is still not resolved. I got a $quote$ from Cap Sante Marine, the local experts who do this a lot, but communication fell apart when we were in Anacortes last week, and then the economy collapsed… they could have had me there, but now I am backing off to re-think cheaper alternatives. I do have one approach in mind, a hack that is a jump up from the original Redneck Bow Thruster idea but still a fraction of the cost of a tunnel thruster.

I have learned much more about handling the boat since the last time I wrote on this topic, including the technique of punching it hard in reverse and then dropping into neutral and using unbiased sternway to improve rudder response. I’ve even had a few sweet docking maneuvers, including one in Anacortes (naturally with no witnesses; isn’t that always the way it works?). But the problems continue… especially when there is wind or current in tight quarters. I’ve grown very fond of anchoring, where this is never a problem.

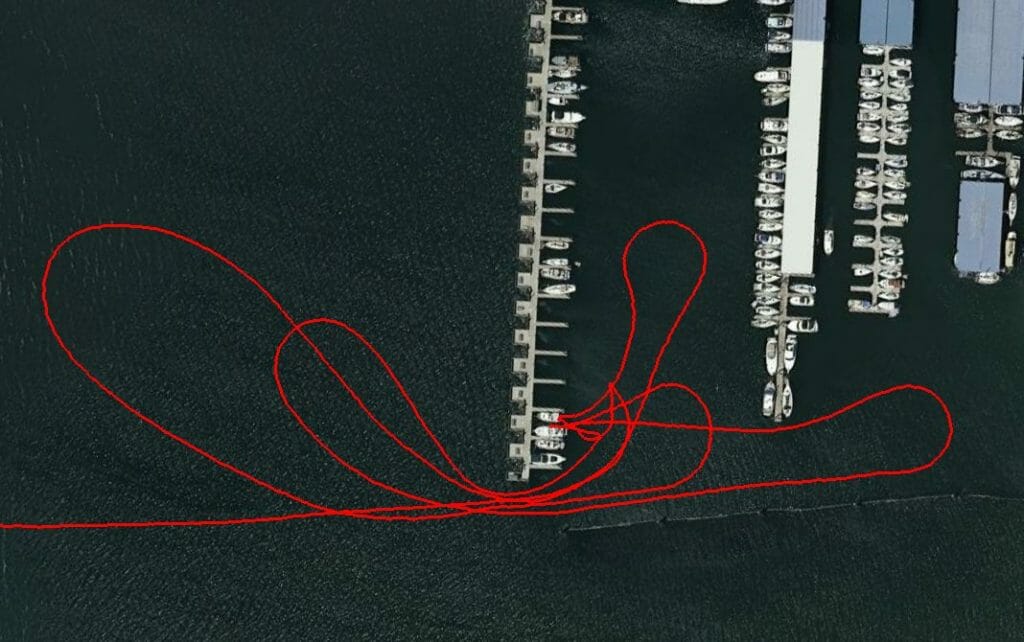

Nomadness actually has a tight steering radius (100 feet), but it is damn near impossible to bring the bow into the wind without having some good steerageway. Tight maneuvering in marinas is thus dangerous, and I’ve gotten used to making sure before going in that there is a way back out. We used it yesterday, twice in fact, making multiple passes at a slip with about 15 knots of wind from starboard:

While I like to think of this as tying a ribbon on the journey, it was a bit tense until we had a line around a leeward cleat and the boat resting on her fenders. Eliminating these little dances at the end of an otherwise exquisite sail is one of the highest priorities over the next few months.

Here we go…

Cheers,

Steve

If you get near Anguilla, in the Caribbean, would be fun to meet you and show you this island. Watched your stuff on and off over the years. Email is my name at gmail.com – Vince Cate